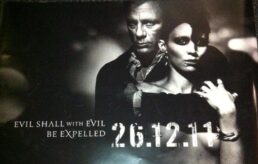

Film Review: THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO (2011)

The Girl with The Dragon Tattoo (2011) Film Review, a movie directed by David Fincher and starring Rooney Mara, Daniel Craig, Robin Wright, Stellan Skarsgard, Christopher Plummer, Max von Sydow, Joely Richardson, David Dencik, Joel Kinnaman, Embeth Davidtz, Goran Visnjic, Julian Sands, Steven Berkoff, Geraldine James, Yorick van Wageningen, and Sahlima.

*A review for The Girl with the Tattoo Dragon can be approached in three ways: A book-to-film review, a different film version comparison, or a regular film review. This will be a combination of all three (I’ve read half the book and have seen all three Swedish film versions of The Millennium Trilogy).*

David Fincher’s The Girl with the Tattoo Dragon is the Let Me In / Let the Right One In scenario all over again. A summary of that scenario is that: there is a book, its first adapted into a Swedish film (in this case, by Niels Arden Oplev) then its adapted into a US film (David Fincher). And like the Let the Right One In / Let Me In scenario, the first film adaptation is far superior to the second film adaptation.

Fincher’s dark palette and history with dark material (Seven, Fight Club) serve him well within The Girl with the Tattoo Dragon but that prowess and expertise can’t save the film from its deficiencies (storyline shifting problems e.g. something terrible happening to Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara) cut to a splendid scene where Mikael Blomkvist (Daniel Craig) is smiling.)

The title sequence for The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo outclasses most if not all James Bond title sequences to date, setting the tone for a great film and a compelling drama/thriller that is never delivered.

The title sequence is what the entirety of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo should have been and what it briefly achieves at times before frustration sets in again. The title sequence is dark, moody, intricately designed, flowing easily from bleak creation to character’s face. There are characters in bondage, in pain, and subdued by restraints. The viewer can’t stop looking at it. It is a black poem come to life, burning tar given wings aflame.

The film that follows has no wings yet valiantly attempts flight through uninteresting flaps of dialog and plot developments. The missing person’s investigation in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is trite, where as the humor, unintentionally or purposely placed, is more memorable (like a misguided episode of Law and Order or CSI).

As book-to-film adaptation (this does not apply to the entire film), The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is mediocre. Fincher changes the ending of the story in his film adaptation and it is to the detriment of the film in two ways: 1.) his ending is not better than the book’s (if Niels Arden Oplev’s film is an indicator of how the book ends) and 2.) it does not fit with or benefit the character that Lisbeth Salander was intended to be when conceived of by author Stieg Larsson. If a change was to be made, it should have: 1.) ameliorated the film and 2.) done like-wise for the character of Lisbeth Salander. Fincher’s ending made Lisbeth more human and hopeful. This is great except that is not who or what her character is. What made Lisbeth such an interesting character in the book was dehumanized she was.

When looking at David Fincher’s version verses Niels Arden Oplev’s version of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, Oplev’s version is not only the winner but also a better adaptation of the source material. There is a multitude of material left out of Fincher’s version included effectively in Oplev’s version. By viewing that version, the viewer can see how seamlessly the inclusion of omitted plot points from Fincher’s version were possible and how they would have positively affected it’s structure.

One plot point that did make it into the film, the infamous rape scene, was mishandled. In Fincher’s version, Lisbeth Salander is an outsider by the way she dresses, not by her personality or her aura. In Oplev’s version, Lisbeth is imbued with far more of the sullen, silent, violent, calculating, anti-social personality she has from the book.

That emotional disconnect makes it easier for her to deal with the rape. Fincher’s Lisbeth does not exhibit that, screaming when frustration boils over earlier in the film.

Because of that, how Oplev’s Lisbeth deals with the rape and how Fincher’s Lisbeth deal with the rape should be different since there is more of a personality in Fincher’s Lisbeth to damage than Oplev’s. They are different people; though they share the same name. Fincher’s Lisbeth should have been in a far greater state of emotional disarray than she is in the aftermath of her rape yet somehow she is as stoic as Oplev’s Lisbeth.

The rapist, the sadist Nils Bjurman (Yorick van Wageningen), sniffing the crack of Lisbeth’s butt is horror movie fodder rarely seen within that misanthropic realm (though Lizard does something close in The Hills Have Eyes remake). Indulging in that olfactory action was true horror: not just the act of rape that it precipitated but the relishing of all its chop-licking accoutrements and salivatory, peripheral elements. It was truly perverted, truly sick, and wholly appropriate for this film and the scene.

The revenge sequence following the rape is another instance of the dramatic difference in the Lisbeths. When Oplev’s Lisbeth stabs the dildo up Bjurman’s rectum by hand, the viewer sees the rage explode on her face, it’s suffused with it (suppressed emotions coming forth), the veins literally popping out of her neck. In Fincher’s version, there are kicks but no revenge intimacy or comeuppance at the level Oplev’s Lisbeth has with Bjurman.

Because of that revenge sequence and the scenes that surround it, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo houses the best performance to date by Rooney Mara, unlike Daniel Craig. Daniel Craig cakewalks the film, the material within giving him no challenge, unlike in Casino Royale. There is nothing for him to do here, nothing substantial or subtle to emote, not even when Rooney Mara is on top of him, vigorously riding away towards sexual bliss (unintentional or purposely placed humor again).

In this version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, the boy/girl sex scenes have been increased while the girl/girl scenes have been decreased. Was this done for the benefit of the Christian America audience or in service of the film’s plot and story flow? I don’t have the answer, only the observation and the conjecture it raises. I do know that homosexual intercourse is what the common American movie viewer sees least on-screen, if we discount films like Black Swan, Chloe, and Brokeback Mountain. This version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo seems to be catering to a male audience while Oplev’s film adaptation has far lengthier and graphic lesbian coital encounters. The ratio between the two is more evenly split in Oplev’s version, making Lisbeth’s bi-sexuality more on-screen then off-screen (the viewer sees Daniel Craig and Rooney Mara engage in sex multiple times but never Rooney Mara and Elodie Yung).

Though not sexual, another commonality that the two versions of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo share is the main villain’s proclivity to be a yenta. Like the previous version of The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, the villain tells the hero why they did what they did, a monologue of un-regret recycled from hundreds of films before it (since it appears in both films, it must be in the book…I assume). Later in the scene, when Lisbeth Salander asks Mikael Blomkvist for permission to kill the killer, the film literally stops (Did she just ask that?) and starts again. If Lisbeth asking for permission was in the book, it should not have been in the film adaptation. The script blows up at that moment, before the Landrover does.

The last twenty minutes of Fincher’s The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo are far looser than Oplev’s. The viewer watches Fincher’s last twenty minutes but doesn’t care about what’s happening. It’s ordinary. The viewer of Oplev’s last twenty minutes is intrigued by the fate of Mikael, the relationship he wants with Lisbeth, and what Lisbeth does briefly while wearing a wig. In Fincher’s version, the wig sequence is long and drawn out, well past its usefulness to the film (think Ruby Rod’s presence in the last half hour of Luc Besson‘s The Fifth Element).

David Fincher’s The Girl with the Tattoo Dragon is a film that should be far better than what it is with this director’s applicable filmography, a literary source to reference, and a prior, well-received film adaptation to possibly view for visual cues and advice.

Rating: 6/10

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!