Film Review: BLACK SWAN (2010): Darren Aronofsky, Natalie Portman, Mila Kunis

Black Swan (2010) Film Review, a movie directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Natalie Portman, Mila Kunis, Barbara Hershey, and Vincent Cassel.

Pressure and its consequences may not have ever been realized with such imagination before as in Black Swan. Director Darren Aronofsky chose the perfect instrument from which to extract his tale. From the outside – from a person that has never seen a live ballet performance – looking in, ballet is all about precision, accuracy, patience, and repetition but when a story is to be told, its about exuding the characteristics of the character they are portraying through movement. Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman) is a scholar of all of these disciplines but one do to her fastidious, sheltered nature. She approaches ballet as a scientist would: with her mind and with her instrument, her body. Her emotions are left out of it and are the cause of her greatest turmoil during her ascension.

This is a by-product and consequence of familial embattlement, a situation that introduces the theme of repression and suppression into Black Swan.

Nina’s overbearing mother Erica Sayers (Barbara Hershey), who both resents and vicariously lives through her daughter, is the centerpiece of Nina’s mental trauma. Her mother deems keeping her daughter, who is in her late twenties, a pampered adolescent and by doing so, controllable, is in her best interest. She knows what’s best, she’s been there, and imposes what she would do, how she would act as a ballerina, pushing Nina hard.

Her daughter’s subconscious response to this is to suppress her sexuality, her social life, all in the pursuit of one day being the Prima Ballerina. Nina’s initial coldness is not by her design. Her mother wants her focused on the work and the work only. As her sole parent and role model, Nina believes in these same ideals.

Reflective of Daniels’ Precious and like many abuse stories, Nina lives with her abuser, her monster, her tormentor, her psychological batterer, her mother. Her monster’s abuse is mostly in-overt rather than overt (the cake incident). Erica’s abuse is the stagnation of her daughter, keeping her emotionally small and fragile, so fragile in fact that she breaks from reality and even forgets self-abuse. When Erica sees hints of the warping, the marginal fragments of genuine mother in her step in. By step in, it is meant into both her domineering personality and into the non-ballet world of her daughter, a major step forward but one if conducted sooner, when Nina was younger, would have done far more good and yielded better results.

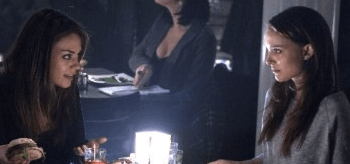

As a visual foil to this theme of suppression and repression, Black Swan’s sexual aspects are depicted as a seductive, provocative, and physically stimulating salivation. These sensual sensory overtures are also present because of the influence and demands of the black swan persona (a character in Swan Lake from the ballet in the film) but in truth “there is another”, as Yoda proclaimed in Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. This third reason shows up in the difference between Nina and newcomer Lily (Mila Kunis), a perceived rival. Nina is attracted to that aspect of Lily that she exudes effortlessly and which she suppresses. Their proximity and interactions stimulate that dormant side of Nina, a coital charisma that encompasses all of Lily. When they are alone and the tension explodes, who the eventual aggressor will be is obvious. That person attacks cunnilingus as a patrician gentleman would whom always savors his exquisite and exuberantly expensive wine and all its surrounding elements before drinking of it deeply and thoroughly. Brava madam.

Darren Aronofsky’s magnificent camera placement delves right into the center of ballet performances, taking the viewer into the intricacies of the stage and dramas underneath it in a way few if any directors have been able to capture before. With the parallels of backstage performer politics, production preparations, and rivalry, the closest film to what Aronofsky has accomplished is probably Forman’s Amadeus.

Nina is a singularity in Black Swan, physically surrounded by others or in the presence of someone yet alone, an island of determination and single-mindedness. Though ambitious, she is not malicious, tearing down others behind their backs as others and she easily could, even when they possess a position she covets.

The pained expression on Nina’s face during some of her performances and when alone is very reminiscent of Leonardo DiCaprio’s in Scorsese’s The Aviator. Perfection is something very important to both of them and anxiety over its attainment is its by-product. Such obsession can manifest itself both outwardly and inwardly. In Howard Hughes’ and Nina’s cases, it conjures both. Their work is their life, almost to the exclusion of everything else – it’s their identity.

Nina’s identity is continually manipulated by the dexterity of Aronofsky’s camera. The viewer is tricked and cajoled by onscreen elements and events as some of what they have witnessed or had come to understand as a truth were a delusion in the protagonist’s mind, unwillful woolgathering so real the worlds between reality, dream, and fantasy become indistinguishable from each other.

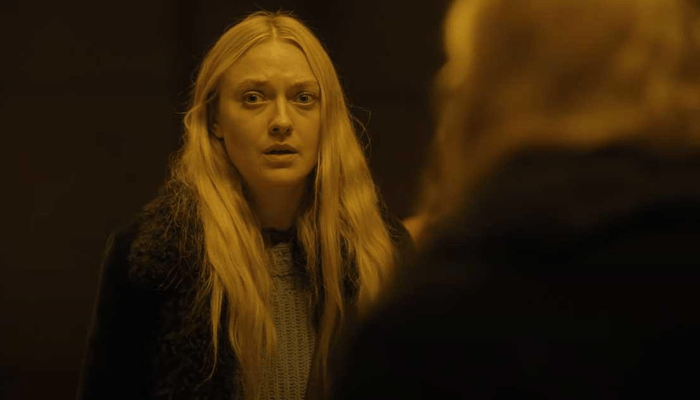

As in the Swan Lake ballet, Nina literally becomes two characters during Black Swan, two realities, one composed of demureness by nature and later one of released, unabashed sexuality, sexuality she had suppressed. Nina glimpses one of those realities at random intervals, especially when stressed (or entering or leaving a stressful situation) yet lives another life, a quasi-normal one most viewers would recognize as their own during the majority of the film. Analogous to good and evil, black and white, this dichotomy between lifestyles and characters epitomizes purity (the white swan) and a lurid transformation into base desires and gesticular sexuality (the black swan).

Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel) continually tells Nina that she needs to exude this, that she needs to exude that as the black swan, that if this vital component is not there, her portrayal is a useless, tepid facsimile, certainly not the black swan. It is only in the finale act of Black Swan, during the section of Swan Lake that the black swan inhabits, that the viewer sees what Thomas was speaking of. The viewer, through Nina’s on-stage performance and the growing awe of her ballet compatriots, sees the black swan’s feathers blossom out of anthoid Nina (Aronofsky making the figurative literal in his film). Nina radiates that oft-missing component in her poise, demeanor, and body language. Everybody sees it, including the viewer, and can’t help but be both impressed and grateful that Thomas was so emphatic and continuous in his pronouncements about black swan. If he hadn’t been, the viewer may have missed the subtleties of the transformation and its importance when Nina is finally able to conjure it.

Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan is a psychological thriller that never drops the ball or ceases to surprise. A supposed companion piece to The Wrestler, both films volley this theme: an ushering out of the old guard and an inundation of new upstarts. Black Swan immolates The Wrestler in many areas and exceeds all of Aronofsky’s previous films as Inglourious Basterds did for Quentin Tarantino and his films.

Rating: 9.5/10

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!