Film Review – SPACEMAN (2024): Launched into Space, Away from Unexploited Territory

Spaceman Film Review

Spaceman (2024) Film Review, directed by Johan Renck, written by Jaroslav Kalfar and Colby Day and starring Adam Sandler, Carey Mulligan, and Paul Dano.

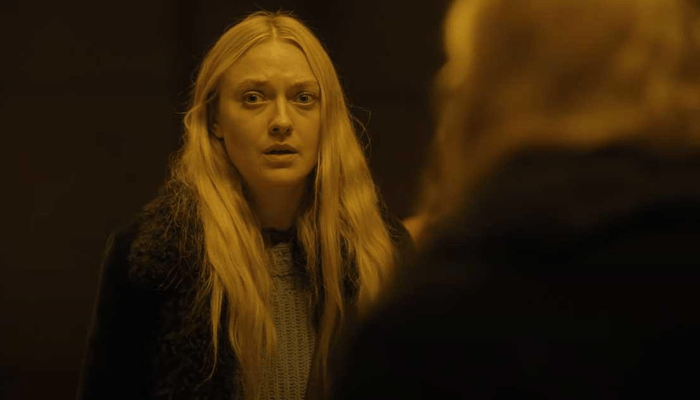

Spaceman (2024) is a science fiction psychological drama directed by Johan Renck and written by Jaroslav Kalfar and Colby Day. It is based off the novel, Spaceman of Bohemia (2017) by Jaroslav Kalfar. The film takes themes familiar to astronaut films and interweaves surreal intrapsychic exploration in the face of a curious, wandering arachnid. It is certainly a rare idea to display the processing of unconscious guilt, childhood loss, and loneliness on the ship commandeered by a Czechoslovakian austronaut, Jakub Prochazca (Adam Sandler) while an alien spider-thing, Hanuš (Paul Dano) pulls out his memories. Of course, it is heart-wrenching to witness a suffering marriage in which Jakub chases after a purple cloud called Chopra near Venus while the pregnant wife, Lenka (Carey Mulligan), waits on Earth. Despite jam-packing the interactions between Jakub and Hanuš with daydream dazzle and, dare I say, psychodynamic psychotherapy, the emotional weight stays there; the impact of Adam Sandler’s albeit passable delivery of his speech-slurring character largely does not exit the confines of the itsy-bitsy spaceship.

What little punch does escape is as ephemeral and insubstantial as one of the many Chopra particles Jakub failed to encapsulate. Mulligan’s forced performance not only provided no chemistry for Sandler, but her opacity, flatness, and generally unromantic demeanor did not provide the strongly lit contrast needed for Jakub’s despondency and loneliness. Mulligan read her lines almost as if from a teleprompter; the repetitive line, “Wherever you go I go, right, Spaceman?” became as irritating as could be. To continue, Jakub’s hard-won epiphanies unnervingly funnel into simply being a better, less workaholic husband. In the process, his relationship with Hanuš becomes strictly functional: the man learned what he needed to learn, so now the alien can die. The emotional intimacy which is supposedly at the heart of the movie fades away into nothingness when the narrative reduces to such realizations.

There are many instances in this film in which the filmmakers explore an interesting concept, but do not make the most of it. As a result, the purpose and meaning of the film are as evanescent and elusive as the Chopra cloud ends up being for the human grasp. For example, if exploring the comet dust was so crucial that Earth had to resort to sending a solo mission from Czechoslovakia, the movie owed the audience an explanation for the sake of buy-in. Was the proximity of the cloud disrupting the atmosphere? Was it simply a matter of ego; a space race to see which country got their first? I understand the point of the film is Jakub’s resolution of generational guilt and embrace of his patriarchal responsibilities in his family, but the circumstances of his mission matter so that again his familial issues have a strong counterpoint against which Jakub can weigh out his manly priorities. Yes, perhaps the novel lacks explanation as well, but artistic license exists for a reason.

Importantly, the film does not further tackle Hanuš’s provocative statement about the universe being both permanent and impermanent. We see the Chopra house a record of everything that has occurred and will occur in the universe at the same time that we witness the alien’s death and Jakub’s transformation. While this juxtaposition begins to illustrate the quandary, it does not find echo elsewhere in the film, save for Hanuš’s strange urn appearance in Jakub’s memories from his boyhood. It would have been very juicy to propose the notion that Hanuš, in some form, was in Jakub’s life prior to the mission and after the South Koreans rescued him. Doing so would have made Hanuš less functional and more symbolic. Frustratingly, the movie did not exploit Jakub and Hanuš’s relationship as a bromance as is done in the Venom films between Eddie Brock and the symbiote. Yes, Hanuš‘s love for Nutella and his idiosyncratic speech will stay with me every time I drink coffee, or, “hot bean water,” as he puts it. I just wish the astronaut had squeezed more juice out of his intergalactic friendship while he could. Perhaps, in holding back so much, Johan Renck delivers the ache of leaving the other wanting more that Jakub is so wont to cause.

Rating: 6/10

Leave your thoughts on this Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire review and the film below in the comments section. Readers seeking to support this type of content can visit our Patreon Page and become one of FilmBook’s patrons.

Readers seeking more film reviews can visit our Movie Review Page, our Movie Review Twitter Page, and our Movie Review Facebook Page.

Want up-to-the-minute notifications? FilmBook staff members publish articles by Email, Google News, Feedly, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, Reddit, Telegram, Mastodon, Flipboard, and Threads.

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!