Film Review: THE HUNT (2020): Edgelord Dialectics That Sees Buzzwords as the Extent of Political Commentary

The Hunt Review

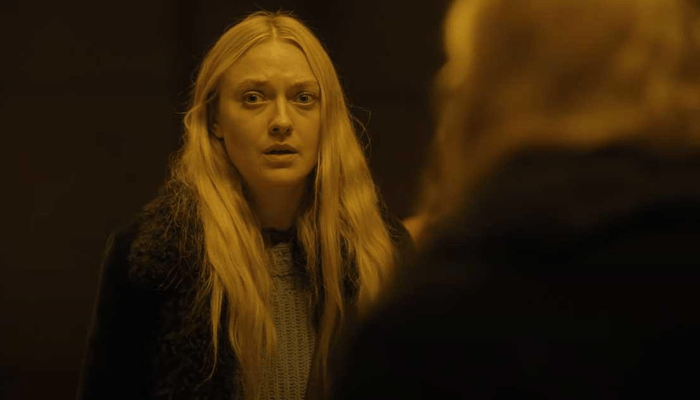

The Hunt (2020) Film Review, a movie directed by Craig Zobel, and starring Betty Gilpin, Hilary Swank, Ike Barinholtz, Wayne Duvall, Ethan Suplee, Emma Roberts, Christopher Berry, Sturgill Simpson, Kate Nowlin, Amy Madigan, Reed Birney, Glenn Howerton, Steve Coulter, Dean J. West, and Vince Pisani.

Throughout his career, or at least the latter part of it (I can’t account for his co-creation of Homestar Runner, as I somehow missed the boat on that one), Zobel has zeroed in on the unspoken iniquities of society and what unfolds when you either stifle or unleash them. The characters in his films can always be boiled down to power struggles – usually multiple struggles occurring simultaneously. And the struggles aren’t just external forces, but internal ones as well.

Compliance sees the manipulation of people’s respect for authority clash with their common sense. They’re forced to decide whether someone’s given title – be it a visible person like a restaurant’s manager, or an invisible person like the “detective” on the phone – is enough for them to surrender their own autonomy, if prompted.

Z for Zachariah follows Anne, John, and Caleb in the wake of nuclear fallout, having to – among other things – consider tearing down Anne’s father’s chapel to build a water wheel generator. The chapel is not simply an emblem of Anne’s faith but the most prominent piece of nostalgia that she has to remember her family by. If she submits to tearing it down, then she’s surrendering her past in order to guarantee an unknown future – one, albeit, with two strangers (both of whom she harbors deep emotional feelings for, and both of whom are going through their own personal, post-nuclear crises).

And now, The Hunt projects a clash of America’s political ideologies distilled to their most superficial signifiers, allowing the violent disdain that they harbor for each other to seep up to the surface without obstruction. In a way, it’s Zobel’s most direct promulgation of his fascination with unspoken iniquities, as the characters show no attempt to mask their innermost feelings. It’s not necessarily an antithesis of his thematic prowess, but it is almost a self-aware parody of it.

What sucks is that Zobel does a piss-poor job of communicating this concept, and more often than not ends up garbling it amidst a bunch of self-aggrandizing, laughable trash.

Z for Zachariah is the exceptional stand-out, in that it’s actually a quiet, contemplative look at one’s struggle to retain humanity after losing everything else. It doesn’t assume much and remains thematically strong by doing so, allowing judgments to be inferred rather than simply proclaimed.

Compliance, on the other hand, is so wrapped up in the incredulousness of its events that it ignores the plethora of relevant peripheral issues at play. Zobel really leans into the whole lack-of-common-sense observation, and rightfully so to a degree. But before every one of the film’s defenders starts linking me the Wikipedia page to the Milgram experiment in the comments, let me say that the film fails to consider the very American variables that fed into the incident at-hand.

One of them is our country’s hyper-militarized police force and our general fetishization of them in the form of blind respect. It also discounts the absolute power that businesses hold over their workers on a daily basis, and how employment is not so much a choice in this late stage of capitalism that we find ourselves in but rather a necessity for survival. That’s not to suggest that all workers willingly denigrate themselves to these extents, but rather that the system we find ourselves in can and has warped people’s tolerances to tolerate such abuses and accept them as normal. Bosses of all sorts have power which we must unfortunately grovel before in order to gain our measly pittances.

But unlike with Zachariah, Zobel posits the shock of the events at the forefront rather than the characters’ unspoken struggles. If there are class-based interpretations to be inferred in Compliance Zobel is definitely not that interested in them, and any analysis of such concepts is but a generous afterthought.

The Hunt is a fallback on Compliance’s surface-level shock that prefers snarky jabs over introspective materialist analysis.

It’s evident that Zobel and writers Nick Cuse and Damon Lindelof have no actual understanding of politics beyond cursory Google searches and glances at Twitter. The film is littered with cringeworthy buzzwords from “snowflake” to “misgendered” to “cuck” to “appropriation”, but only to the extent that they act as verbal set dressing. There’s no honest attempt at reckoning with the weighted concepts behind those words (and, in the case of one of them, the dually racialized and sexualized connotations it carries) but rather just for audiences to feel a sense of self-importance for recognizing them because – like a pair of the liberal “elites” mention after a recent slaughter of “deplorables” at their gas station – they heard it once on NPR. Such a superficial interpretation of politics is so disconnected from reality that it can’t even function as satire because it barely understands how real-world power dynamics craft political identity.

Case in point, leave it to these liberal writers to put such a politically-left-charged word as “comrade” into the mouths of the elites, suggesting that anything that isn’t blatant conservatism is automatically socialist. (Isn’t that the same line of argument that the political right used throughout both of Obama’s terms? And continues to use to this day?)

However, The Hunt has some good things going for it. When the deplorables wake up in an unknown field and are forced into a shootout, Zobel lights the spark that sets off the film’s chain reaction of non-stop carnage. Unlike Crystal (Betty Gilpin) who creates a makeshift compass with a hairpin and a leaf, we’re left to flounder about the world without direction or clarity. The speed at which the characters are killed off is so rapid that we feel lost in the game ourselves. Gilpin, for what it’s worth, gives a terrific performance that goes unmatched. The subdued ferocity she imbibes into Crystal is both terrifying and awesome in a way that few action leads can muster. Gilpin’s reserved movement adds to Crystal’s mysterious demeanor, and reinforces her resourcefulness in limited situations. (Her fight scene with the elite’s ringleader, Athena [Hilary Swank], shows this off through effective, constrained choreography.)

Also, if anything, Zobel, Cuse, and Lindelof accidentally trip into potentially meaningful critique of the liberal class through, ironically, the sheer superficiality of it all. The elites’ use of buzzwords as a sort of virtue signaling is a mask they don whenever it’s most convenient for them. Optics are more important than actions, and they’re willing to discard them when either their own class interests are at risk or their own pride is threatened. Reference takes precedent over moral commitment – it doesn’t matter if they actually believe what they’re talking about, as long as they look like they do. Take it from me, your own irony-poisoned Internet addict who spends way too much time on Twitter: liberals not comprehending their own hypocrisy when it comes to “jokes” is more common than you’d think.

But as an overall film, The Hunt pushes the mainstream media’s post-2016 argument that identity politics are to blame for the right’s continued surge. The idea that the left’s focus on inclusive behavior alienates too many people is just a right-aligned talking point to further deny people of their humanity. (Ironic, seeing as Zobel’s films are all about society’s humanity to some regard.)

This is such a disillusionment of the real world and a misunderstanding of how people communicate in the digital age. Of course people don’t actually call you out on misgenderings and other microaggressions in real life, because the threat of violence from misogyny, racism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia are extremely prevalent. Real life can’t offer the same (somewhat) anonymous safety that online spaces can. But seeing as liberals are the same class of people who think phrases like “bed bugs” are slurs, it’s easy to see how they’d willingly read every Twitter spat as a direct correlation to everyday interactions.

As such, the film functions not only as an appeasement from liberals to conservatives, but an appeasement from liberals to liberals themselves. It’s a reassurance for the edgelords among them, those that know aligning with conservatives is career suicide but who still want the right to deny marginalized populations their respect and autonomy and not be called out for it.

And thus we’re back at the film’s flawed central conceit. Zobel, Cuse, and Lindelof take the centrist, liberal approach that politics is nothing more than a teams sport. This sort of interpretation of vague left- and right-leaning tendencies gives credence to our own president’s infamous argument that “both sides” are to blame for the current state of affairs. It’s adjacent to the spineless liberal cry for normalcy that opines for things to go back to how they used to be. I hate to break it to you, guys, but only one political wing is fighting for the overall betterment of society – for universal healthcare, and civil rights, and economic justice, and environmental protection. And I hate to break it to you further…but liberals don’t often fall in that category, either.

This focus on optics allows for liberals – both the filmmakers and the viewers alike – to conveniently ignore the material consequences that led to such schisms in the first place. Zobel, Cuse, and Lindelof aren’t interested in how capitalism preys on the working class and pits people against each other while the elite horde all the resources. Once again, Zobel isn’t interested in the peripheral variables that feed into the primary conflict. The Hunt is not concerned with unpacking biases and uniting against a common enemy. It is just another liberal assuagement for the status quo, disguised as subversive knack.

But hey, at least The Hunt’s liberals have moved back to the classics of 1984 for their political metaphors. Thank god they finally put Harry Potter back on the shelf.

Rating: 3/10

Leave your thoughts on this The Hunt review and the film below in the comments section. Readers seeking to support this type of content can visit our Patreon Page and become one of FilmBook’s patrons. Readers seeking more film reviews can visit our Movie Review Page and our Movie Review Pinterest Page. Want up-to-the-minute notifications? FilmBook staff members publish articles by Email, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, and Flipboard.

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!