Film Review: TRUE HISTORY OF THE KELLY GANG (2019): Australian Historical Revisionism That Champions The Fight Against Colonial Power

True History of the Kelly Gang Review

True History of the Kelly Gang (2019) Film Review, a movie directed by Justin Kurzel, and starring George MacKay, Orlando Schwerdt, Charlie Hunnam, Essie Davis, Claudia Karvan, Russell Crowe, Jack Charles, Nicholas Hoult, and Thomasin McKenzie.

Regardless of opening disclaimers such as “Nothing you’re about to see is true”, a film can still speak to societal truths. Justin Kurzel’s latest, True History of the Kelly Gang, is just that: a historical revisionist tale of one of Australia’s most infamous outlaws that’s also about standing up to violent oppression and speaking your truth – even if other people won’t listen.

Adapted from Peter Carey’s novel of the same name, Kelly Gang is a fictional account of the life of bushranger Ned Kelly in late-19th-century Australia. Born to a transported Irish convict (Gentle Ben Corbett) and a poor mother, Ellen (the terrific Essie Davis), Ned Kelly (Orlando Schwerdt) is highly attuned to the inequities of his frontier life. As the oldest of his multiple siblings with an innocuous, inebriated father, Ned is made into the main breadwinner for his family – or, actually, “beef”-winner, as he wrangles up a stolen cow and drags its bloodied hinds home for dinner. Ned’s manliness is won by providing for his family, a designation Ellen can’t stop rubbing in Mr. Kelly’s face.

After a local constable (Charlie Hunnam) arrests Mr. Kelly for the stolen cow and he dies in prison, Ellen gets cozy with fellow bushranger Harry Power (Russell Crowe), to whom she sells Ned under the guise of a hunting mentorship. But it’s not animals that Harry is hunting, and Ned is stunned into anger when he witnesses his first face-to-face acts of brutal violence. Ned runs away and refuses to take part in the violence, but his criminal involvement catches up to him and he’s thrown in the slammer.

Upon his release, the now-grown Ned (George MacKay) returns to his mother’s home to find his siblings grown up and a Yank suitor (Marlon Williams) moving in on his mother. Despite his post-prison bouts of violence through underground fighting rings Ned still detests it, and tries to find a peaceful way to resolve his brother Dan’s (Earl Cave) cattle wrangling charges. But an initial agreement with a new constable Fitzpatrick (Nicholas Hoult) goes awry, pushing Ned to the brink and testing the strength of his non-violent convictions. It’s then that Ned must embrace the rebellious spirit of his father’s past and fight back, lest he fully succumb to the state power that’s ruled over him for his entire life.

It’s strange watching a movie like this as anti-police brutality protests unfold all over America. Obviously the film and the current events are not equal parallels, as Ned’s fight does not even take place in America and he is not fighting back against racist oppression. But there is the underlying current of colonial violence that threatens all those who are not in the top social strata of white political powerholders.

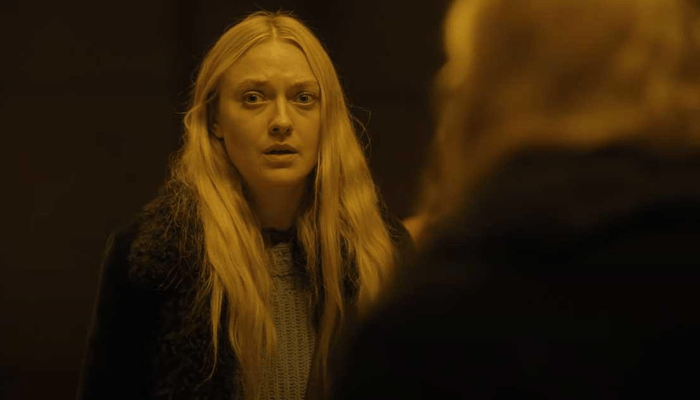

Ned’s father’s ex-convict status taints the entire Kelly family’s reputation, as it did for so many others who lived out in the Australian bush. His Irish ancestry – and the transport status that implies – provokes disdain amongst the elites bordering on nationalism and xenophobia. And Ned’s poverty is an easy target for the petit bourgeois, who wield their influence and pit the lesser members of society against each other for their own entertainment. (The way the fight club bystanders barely flinch when splattered with one of the men’s blood, and continue to laugh and cheer, speaks scathing mounds.) Even abuse of police power outside of aggravated assault is made starkly apparent, including a third-act scene in which Fitzpatrick twirls a loaded pistol in a baby’s face as a shellshocked Mary (Thomasin McKenzie) pleads for peace.

Again, this aforementioned parallel is not an equal one, and as such it is not made to cheapen nor usurp the anti-black racism that African-Americans continue to experience. Such historical horrors particularly done in the name of American empire are incomparable. But Kelly Gang’s focus speaks to a shared sense of colonial violence brought about by Western imperialism – particularly from Britain – in its centuries-long conquest of much of the world. Even the subplot of Ned’s writings to his unborn child feeds into this fear of colonialism, and speaks to the need to acknowledge your own history before it’s rewritten to adhere to the affluent narrative.

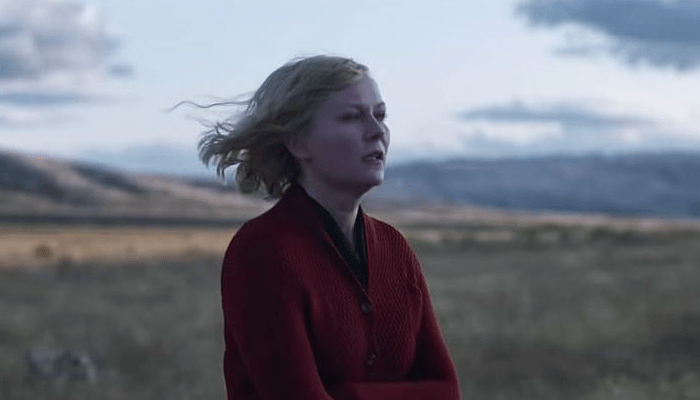

Kurzel taps into this underlying fear through his cold, misanthropic approach. With Ari Wegner’s washed-out, shadow-heavy cinematography and Jed Kurzel’s brilliantly ominous score, Kelly Gang leans into horror-movie sensibilities to bring forth said horrors of history. Even in its lulls there’s an unshakable sense of anxiety – the dissonant strings calling forth visceral rage from deep within ourselves, and the strobe effects and spot-lit horse rides evoking an eerie sense of the unreal. Mixed together, it’s a dark and gritty feeling of constant discomfort – the equivalent of smearing dust into an open wound.

It’s not much different in style from Kurzel’s Macbeth adaptation, or even his flawed (but somewhat commendable) Assassin’s Creed. What puts Kelly Gang a step above the others, however, is its incredible ensemble who pulls off their complex characters with such texture and finesse. The aforementioned Essie Davis is near-unrecognizable as the Kelly matriarch who pits her son’s emotions any which way to benefit herself. Davis’ firm stoicism makes her all the more intimidating, and her outbursts so much more distressing. Nicholas Hoult is the other standout here, whose chivalrous camaraderie and silver-tongued speak is a ploy to cover up his greedy and violent (and possibly psychosexual) intentions.

Of course, Kelly Gang has a few faults. The character motivations and thematic cohesion starts to unravel before the finale, making Ned’s last revolutionary tactics a bit difficult to follow. The random punk needle drops are amusing, too, but they also clash with – and distract from – Jed’s otherwise cohesive score. It’s also a bit difficult to make out what statements – if any – Kurzel and screenwriter Shaun Grant (and perhaps even novel author Carey) were attempting to make on masculinity, gender identity, and possibly even queerness.

There’s a certain tenderness that Ned’s non-violence suggests, evident by his own discomfort at confrontation as well as the chidings of his mother for not being aggressive enough. And the Sons of Sieve’s practice of donning flowy dresses is definitely a distortion of gendered expectations, a battle tactic that they use to their advantage. As Ned’s brother Dan says, the enemy “is scared of what they don’t understand”.

Perhaps this is a waxing on the fluidity of masculinity – that embracing destructive violence will be its downfall, or conversely, that femme presentation does not automatically denote timidity. However, the Son of Sieve’s wardrobe feels less like a radical reconstitution of clothing symbology and more like a usurpation of the feminine for the masculine – an aggressively conquering vibe. Similarly, while having Ned’s softness and apprehension for violence mirrored in his quasi-lover Joe Byrne (Sean Keenan), Joe’s reluctance sort of paints the film’s most concrete emblem of queerness as timid and constrictive. If this is just meant to be a broader dissertation on the overall messiness of revolution, then my read might be too deep. However, while we’re talking about current events in this review, it’s important to remind everyone that we’re currently in the midst of Pride month – a time in which we honor a movement spurred to life by proactive retaliation against oppressive powers. Such a read in which representation could arguably feed into a digressive trope is not all that far-fetched. But again, Kurzel and Grant’s analyses of these points makes them too vague to thoroughly decipher.

Despite its messiness, True Story of the Kelly Gang is a stark look at righteous anger against violent, controlling forces. It’s about attempting to tell your story in the face of adversity, even when you’re certain it’ll eventually be co-opted. It’s about fighting for that smidgen of hope for a better society, despite the overwhelming barriers of cynicism ahead of you.

And it violently scratches that cinematic itch.

Rating: 7/10

Leave your thoughts on this True Story of the Kelly Gang review and the film below in the comments section. Readers seeking to support this type of content can visit our Patreon Page and become one of FilmBook’s patrons. Readers seeking more film reviews can visit our Movie Review Page and our Movie Review Pinterest Page. Want up-to-the-minute notifications? FilmBook staff members publish articles by Email, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest, and Flipboard.

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!