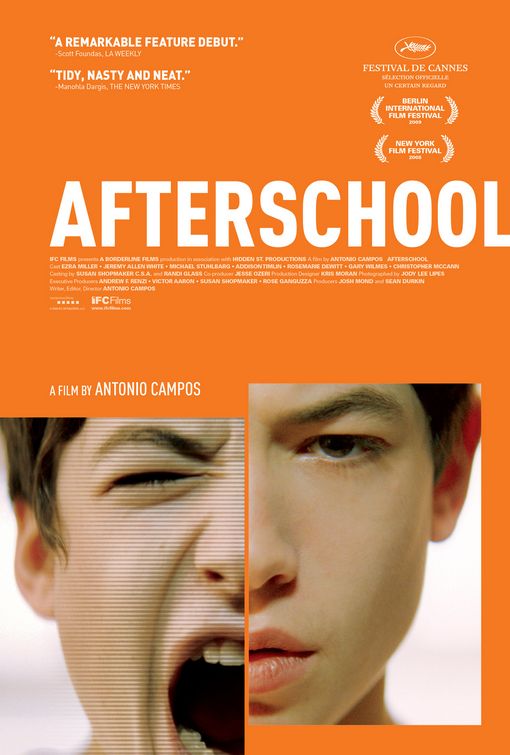

Film Review: Afterschool

Afterschool’s opening montage is more of an accusation than a procession of images and videotaped situations. The unpoliced internet, its content, and the nature of man to watch a train wreck while it happens and then to stand still, stunted in mobility, transfixed as the grim aftermath occurs, are what are really on display. As the film unfolds its tale, the viewer sees this happen again and again in small and large venues. Desensitized to human horror, male high school students watch the videotaped tragedies again and again through illicit means.

Not only is the main character, Robert (Ezra Miller), a voyeur, by director Antonio Campos’ constant camera placement behind his head or over his shoulder, the viewer becomes one as well.

Director Antonio Campos perfectly captures the mindset of the adolescent male while Robert is in his room alone or in class. A comely female teacher dissects Shakespeare as she is visually dissected through tastefully salacious images of her anatomy.

Robert tells the school counselor that he likes watching bits, not wholes, flashes of real life on the internet. Those segments are exactly what he becomes a part of on two occasions during the film. When the watchers become the watched is when the film takes an interesting turn and it happens unobtrusively right in the middle of Afterschool.

When Robert is alone with Amy (Addison Timlin), a girl he is secretly smitten with, and they kiss, the camera in the room does not even capture it, a liberty that should not only be attributed to this film’s independent origin. This happened because the kiss is unimportant but its still treated as personal. Campos cleverly used his camera placement to show the viewer these facts. It’s still Robert and Amy’s private moment, their first kiss, even though its on screen.

After the tragedy, parental eyes are on Robert and he is soon asked to make a memorial video: the voyeur becomes the filmmaker, the architect of something that will be seen by others, a complete role reversal. What Robert creates is something true to the victims of a tragedy. The viewer knows it but the school administrator is incensed by it, having desired a Hallmark card with music, a falsehood, as false as the images and skewed reality presented in high school yearbooks. Adolescent life is rarely that black & white. Soon Robert is even the subject matter of a video, reduced to a nameless student in a bellicose scenario, clicked and re-clicked again, the online viewers having no context or back-story to why it happened nor do they really care.

The emotional upheaval in the Afterschool causes bends in the life road of characters, which causes other deviations, detours, alternate and increasingly unexpected decisions as the film progresses. One refreshing aspect of Afterschool is that age appropriate actors and actresses were used. As such, when hard decisions and consequences for actions present themselves, their actions underneath that weight are more interesting to observe.

One such observation is of Robert’s self-flagellation. The viewer watches him as he slaps himself over and over again, trying to feel something after the tragedy has transpired. Part of him knows that he should but he is numb: his pale skin, placid face, and the bland, out of focus backdrop enumerate this internal continence. His numbness is not situational but a persistent state. The degradation porn, violent war images, and constant replays of the Talburt twin’s death via cell phone camcorder footage by he and his friends are early and latter examples of this.

Unlikely the majority of teen dramas, Afterschool presents a dramatic microcosm of subversive high school life. Less self-indulgent and moving quicker than Van Sant’s Elephant, the real world playground of Afterschool is Christian Nestell Bovee’s quote personified: “No man is happy without a delusion of some kind. Delusions are as necessary to our happiness as realities.”

Rating: 9.5/10

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!