Film Review: Enemy (2014): Which is Ms. Muffet? Which is the Tuffet?

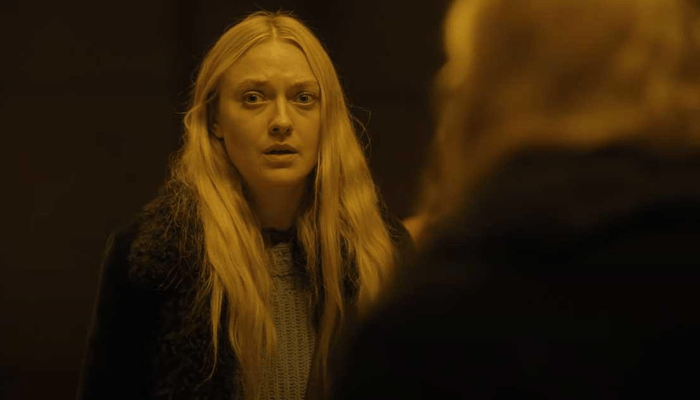

Enemy (2014) Film Review, a movie directed by Denis Villeneuve and starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Mélanie Laurent, Sarah Gadon, and Isabella Rossellini.

When simple living history teacher, Adam (Jake Gyllenhaal), allowed for a break in his routine, and had a movie night, the result was the discovery of a perfect double – an actor named Anthony (Jake Gyllenhaal). Excited curiosity became something both darker, and unexplainable, however, once Adam & Anthony realized that there was more than a likeness between them. Darker, still, when their respective partners, Mary (Mélanie Laurent), and Helen (Sarah Gadon) were drawn into the fallout of Adam & Anthony’s catalytic interaction.

Oh, yes, lest I forget: spiders.

Enemy presented a small, but compelling cast; an inscrutable plot, behind a simple premise; visuals both beautiful and disturbing; and all at a relatively short running time of 90 minutes. Jake Gyllenhaal was well cast, as both the simple idealist, and the hedonistic cad, likely found behind the amiable face of either of his characters. Sarah Gadon managed to project a certain authority through her character’s insecurity, which proved useful to the film – as I may have seen it (I’ll explain that one, really). Mélanie Laurent may have had the smallest, least appreciable role, in the film, but she always manages to bring a larger presence to whatever scene she is in.

The true quality of the film, for better or worse, came from the creative choices of director Denis Villeneuve, and screenwriter Javier Gullón. The first, and most inescapable question, regarding Adam and Anthony, was who were they, in relation to each other, and whose story was it. The answer to that question could have been provided by any number of clear clues. A conversation between the mother (Isabella Rossellini) and her only son, or the fact that there were never any witnesses to Adam and Anthony sharing the same space, for example. Changes made to José Saramago‘s novel, however, left me less interested in finding answers to this question, than in the notion that there might have been a better question to ask.

Who do you think is your worst enemy? Here’s a hint:

Your worst enemy will have a familiar face.

Once past the initial shock, the great mystery became more than just seeing oneself in a completely different light. Adam’s fixation on Anthony sidelined Mary’s already marginal place in his life. Adam’s mere existence re-opened old wounds for Helen. The escapism, to Adam and Anthony’s dealings with each other, unhinged their partners’ lives, as much as their own. This resulted in just enough chaos to invite deciphering, where deciphering shouldn’t have even been necessary.

In all the monotony to Adam’s life, the two routines that stood out was his apparent disassociation with Mary, as anything other than a sexual object, and his repetitive class lecture on the facilitation of totalitarian regimes. There was no way to get past these; there had to be more to those moments than just a demonstration of the tedium & dissatisfaction that would fuel his curiosity about Anthony.

Both Adam and Anthony were driven by a need for change, but for different reasons. For Adam, it might have been the need to try something new, or different. For Anthony, it seemed to be a need for the freedom to go back to old vices. The common thread, here, was desire; and while it may not explain the story behind Enemy, it may, at least, have been the key to understanding how the primary players fit into it.

Your worst enemy is the one that compels you to come its way by choice.

Anthony had every right – and opportunity – to write off Adam, but chose to meet. Adam had every right to dismiss Anthony’s plan to exploit their likeness, but did not so much as attempt a rebuttal of Anthony’s claims over him. It was as if their efforts, to exercise some control over a predetermined existence, was in turn predetermined. They believed those choices were theirs to make, however, and that was all that mattered.

The domestic element, represented by Mary and Helen, could have been regarded as a controlling force, as well. Despite her evident dissatisfaction with their routine, Mary maintained her relationship with Adam. Even after what could have been considered attempted date rape, sex seemed to be all there really was to it. Mary’s role, as Adam’s handler, provided Anthony with an out to his own relationship box. Mary’s willingness to be a sexual object, however, did not extend beyond Adam. Her reaction to Anthony gave no regard to the likeness, only to the fact that he wasn’t Adam.

Helen, on the other hand, seemed more interested in curbing Anthony’s sexual appetite – an appetite that he seemed to have in common with others around him (the sex club, and his doorman’s new found fixation on it). However disturbed she was, by the notion of Anthony slipping through her fingers, she seemed even more disturbed by meeting Adam. Is it possible that Adam’s contentment reflected just how far Anthony had already slipped from her grasp? She not only saw through Anthony’s scheme, she accepted it. Perhaps this was an acknowledgement that Anthony was a loss; perhaps it was an attempt to salvage Adam through a proven method – even if his own mild discontent interrupted the afterglow.

If the firm grasp Mary had on Adam left her incapable of dealing with Anthony’s flexibility, Helen’s need to match that flexibility allowed her to reassert a grip on the less sexually restless Adam. Whatever they had gotten into, and whatever the outcome, one or both of these men had been convinced that there were choices to be made, and made them.

Your worst enemy looks like the things that happen to you, while you are busy making other plans.

The first parallel to come to mind, while watching Enemy, was Kafka. By the end of the film, however, I kept thinking of Orwell, and his use of animals to parable totalitarianism. Animals – particularly vermin – have always been a propagandist tool, both for and against a totalitarian state. It would be easy to cite totalitarianism as the hidden message, behind Enemy; much of what Adam had been lecturing about could have been very subtly at work for either/ both he & Anthony. The problem, however, would be in determining who was protagonist, who was antagonist, and which (if any) had the powers-that-be, symbolized by spiders, behind him.

Your worst enemy comes from the Sleep of Reason.

The totalitarian subtext could just as easily be supplanted by something less Human in design. Here’s a question: how would you have felt about The Matrix, had it been stripped of its guns, wire-fu, and Morpheus’ exposition on its setting & events? Would it have been enough to get a feel for Mr. Anderson’s plight, without any actual mention of the Matrix, itself? Likely not.

The dream like quality to Enemy could have been literal. Much like dreams are the subconscious mind’s effort to show us what we are unable/ unwilling to see, through conscious eyes, Andy/ Anthony may have been presented with a series of inconvenient truths, rendered incomprehensible by their own resistance to those truths. From the viewer’s perspective, these would make even less sense, as attempting to convey the gravity of one’s dreams to others often fails.

The ongoing, slow boiled frog of a nightmare, unfolding on screen, could have been supernatural in nature. A single man’s navigation through Purgatory, or perdition, while being confronted by his own misdeeds in life – occasionally catching a glimpse of his jailers. Either scenario would explain the heavy symbolism displayed (the spiders were obvious – the webs were more subtly inserted into various shots). In the end, however, it really didn’t matter. The nature of the nightmare was clearly less important than its effect.

The beauty of Enemy was in its inconclusiveness – but only from a given angle.

As a psychological thriller, Enemy was frustratingly unsatisfying; it left too little impact, and did not make enough sense to really thrill. As a psychological parable of socio-political manipulation, however, it could be genius. Less subtle parables, such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or 1984, were that much more effective for their open endings. The real world threat they represented was ongoing; so a neat & happy ending would have been a disservice. If the point of Enemy was that there was one or more persons – being or sharing two sides of one coin – caught up in the web of an external force’s machinations, but without the slightest clue that this was taking place, it stands to reason that the viewer may not be entirely entitled to know this, either.

The duality of Adam & Anthony (and the spiders, in particular) may leave casual viewers sufficiently confused and creeped out at the film’s face value, as with films like Rosemary’s Baby. For those who see a deeper, more sinister meaning behind them, however, Enemy may prove absolutely terrifying.

So, have you figured out who your worst enemy is? Here’s one final hint: it’s the same as everyone else’s.

7/10

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!