Film Review: THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL (2014): Tripping to St. Ives

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) Film Review, a movie written & directed by Wes Anderson and starring Ralph Fiennes, Tony Revolori, F. Murray Abraham, Mathieu Amalric, Adrien Brody, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum, Edward Norton, Saoirse Ronan, Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman, Tilda Swinton, Jude Law, Tom Wilkinson, and Owen Wilson.

The Grand Budapest Hotel may have been Wes Anderson’s most ambitious effort, to date; and whether a fan of his or not, anyone familiar with his work should know that says a lot. With that in mind, I’ll try to keep things simple.

The Grand Budapest Hotel was first presented as a book. It’s author, introduced as a seasoned writer (Tom Wilkinson), first recounts how his younger self (Jude Law), while staying at the once iconic hotel, became a dinner guest of its owner, Zero Moustafa (F. Murray Abraham). As a fan of the Young Writer’s work, Moustafa arranged to tell the tale of how he came to own the hotel, as well as how he came to be the man that he was.

Both of those stories centered on young Zero’s (Tony Revolori) initiation, as the hotel Lobby Boy, under the supervision – turned mentorship – of hotel Concierge, Gustave H (Ralph Fiennes). Gustave’s meticulous attention to both detail, and the needs of the hotel’s guests, extended to some more personal servicing of certain members of the clientele. The sudden death of one such cherished guest, Madam D (Tilda Swinton), brought Gustave and Zero into the matter of her estate, Schloss Lutz’s inheritance proceedings. When Gustave was declared the inheritor of a priceless painting, he became the matter of the proceedings, as far as eldest son, Dmitri (Adrien Brody), was concerned.

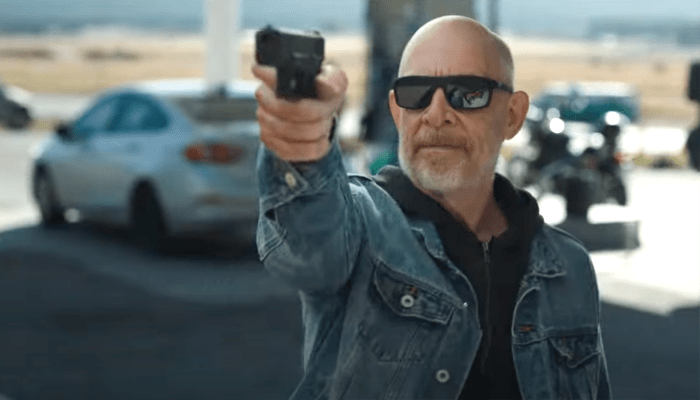

Gustave and Zero made off with the painting, but when accused of Madam D’s murder, Gustave became the center of a manic circle chase caper, involving Zero, Zero’s love, Agatha (Saoirse Ronan), a sympathetic but dutiful Military Police officer (Edward Norton), Schloss Lutz butler, Serge (Mathieu Amalric), Schloss Lutz attorney, Kovacs (Jeff Goldblum), Dmitri, Dmitri’s enforcer, Jopling (Willem Dafoe), with just enough room for jailbreaking convicts, game changing pastries from Mendl, and a Concierge order, called The Society of the Crossed Keys, fronted by M. Ivan (Bill Murray). I may have missed a nesting doll, or two.

So, much like a solo traveler’s (highly surreal) journey to St. Ives, The Grand Budapest Hotel introduced an ever widening circle of colorful characters. At best, they made the film’s core story well worth telling. At worst, they may distract some viewers from what that story actually was.

One factor, that may prove distracting to some, was Ralph Fiennes’ performance. Gustave slipped so smoothly, so seamlessly, between charm and aloofness, genuine warmth and smarminess, extraordinary control and utter panic – all done at such a fluid, snappy pace – that we were left with a lead character more earnest, than heroic, and the film was better for it. His flaws made him as dependent on the supporting cast as some of them were on him, with the communal feel of the film’s characters helping to realize the hotel’s fictional setting of Zubrowka. The cast chemistry, that seems to come from being in multiple Anderson productions, might have helped in overlaying their character roles.

Part of the Wes Anderson experience has, admittedly, become spotting the usual players; and certainly, the usual suspects, like Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson, and (of course) Bill Murray were present. What is important to note about the acting, for Hotel, is that there was a notable lack of range. Every role was portrayed by the respective actor as the actor, not the supposed character. In other words, there were no discernible efforts to act or sound like early 20th century Austria-Hungarians; instead we got the likes of Goldblum, Norton, Wilson – even Harvey Keitel – all being themselves, just in costume. Here’s the thing: I think it was both deliberate and worked for what Anderson may have had in mind.

The Grand Budapest Hotel story unfolded like something of a relay, with each of its actors taking turns carrying it forward. In this respect, I suppose it would be no more of a requirement for them to put on a show for Hotel, than, say, had they been telling tales at a campfire, or anecdotes at the dinner table. Of course, an anecdote at the dinner table is exactly what Hotel amounted to. It occurred to me that Anderson simply wanted viewers thinking of his cast more as storytellers, themselves, speaking in their own voices, rather than actors trying to sell us a fantasy.

For all its fantasy stylings and whimsy, however, there was much more to The Grand Budapest Hotel‘s adult content than the usual Wes Anderson affair. Beyond foul language and sexual subject matter (more prevalent, here, than in most of his other works), Hotel was not so much a black comedy, as it was a light-hearted suspense thriller. The plot, behind its coming-of-age tribute story, revolved around murderous greed, a militarized state, a priceless painting that holds an even more valuable secret, and an amoral (if not sadistic) pursuit, all set against a back-drop representing World War 1, and the end of the Habsburg Empire, through the rise of the Nazis, and World War 2.

Those elements all combined to create set pieces of intrigue and chases that reminded me of films like The 39 Steps. For this aspect, Hotel made ample use of Brody and Goldblum, representing polar opposites in view, regarding the letter of law. It was into this divide, and the chase for Hotel’s ultimate prize, that came a memorably villainous role for Willem Dafoe, as Jopling. While none of the thriller element characters were played for laughs, the steady escalation in tension, menace, and violence (owed mostly to Jopling) did provide some nervous laughter moments (as with the culmination of Jopling’s errands, ironically enough).

The execution of the film’s action, while ranging from brutal to hilarious (or just brutally hilarious), brought the musical score to my attention. Alexandre Desplat‘s work for Moonrise Kingdom was a highlight for that film, as it perfectly represented its layering of plot and characters. For Hotel, his music conveyed a rhythm to the action; but it seemed as though some of the characters were actually conscious of this – acting accordingly, in order to get the better of pursuer or quarry. Such breaks in rhythm brought relief to moments of impending dread, and bad ends to would-be narrow escapes.

The beauty of The Grand Budapest Hotel was in its ability to deliver smiles, through acts and moments of joy, amidst all the bad behavior. The revolving juxtaposing of Gustave and Zero, off-the-cuff & earnest remarks, even the vicarious thrill of the first bite into a Mendl cake, all serving to break tension. A lot of that joy, however, came from reoccurring reminders that good deeds not only sometimes go unpunished, but are rewarded. Those moments served to validate a core premise of the film: that actually believing in the need to be both mindful and accommodating of others – the core principle of the Concierge – makes a well run hotel a model for the rest of the world (The Society of the Crossed Keys serving to espouse this as universal). Gustave’s attention to detail and considerate attitude, qualities that made Grand Budapest what it was, served him well, under the harsher conditions beyond its walls. Unfortunately, Zubrowka represented both a time and place where the virtues of people like Gustave, Zero, and Agatha win the day, but was ultimately doomed to a fabled memory.

The Grand Budapest Hotel was a fable that delighted, in its unapologetic pride in being a fable, but more than that, it could be considered a fable about fables. There was no moral to the story (unless you count the whole karma angle); no attempts to create a singular mythology, where all players conform to whatever language, norm, or mannerism characterizes the setting; certainly no storybook ending. Heavier elements, like the parallels to Nazi Germany, may have been largely skimmed; but the larger theme, in that regard, involved the loss of the gentleman age, which had been at the very core of Gustave’s being (and thus, by extension, Zero’s ascension). The nature of that which ended it was irrelevant; all that mattered was impressing upon us how great a loss that end truly was.

Even with its darkest turn coming just after the main plot’s resolution, leading to an abrupt and somewhat unsatisfying end to that particular story, the actual story told – the dinner anecdote that predicated it all – was fully completed. For viewers who might have lost sight of that fact, or had become so engrossed by its supporting elements, I would suggest the same measure of gracious acceptance as the Young Writer no doubt had to resort to. He was offered a tale of how Zero Moustafa came upon his fortune, and ownership of The Grand Budapest; he had to settle for precisely that. We, the viewers, were simply asked to share his seat at Moustafa’s table.

This was only a journey to St. Ives, after all.

9/10

Related Articles

FilmBook's Newsletter

Subscribe to FilmBook’s Daily Newsletter for the latest news!